Valor

By Bridget Floyd

Ron Hemenway, or the Sergeant Major as we like to call him, is a dedicated and caring father. He is a devoted husband to my mother with 40 plus years of marriage. He served four times in Iraq post 9/11 as a civil servant even after he had retired from the National Guard as a Sergeant Major with 26 years of service. He was the youngest person ever to be promoted to SGM in New York State. When I was nine years old he received the medal of valor. I didn’t know truly what it meant or that it would grow to become the symbol I use to define my father. Even now, as he battles cancer at the end of his life, a cancer his doctors believe to be caused by his exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam, I see that medal encompassing not just one incident, but his entire life.

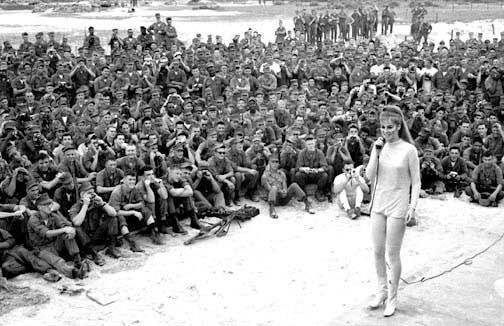

My mornings during childhood usually began the same way and this particular Tuesday of my ninth year was no exception. I heard my father in the kitchen, ironing his uniform before work. The bitter smell of shoe polish and burning wood from our potbellied stove pervaded our small house. While he was showering in the bathroom across from my room, I stumbled out into the kitchen to see the shiny black shoes on the chair. They were always so shiny I could see my reflection. I ate my bowl of Lucky Charms and watched him fix his coffee in his sharply creased, dark green pants and stiff light green, short sleeve shirt. He kissed me goodbye before putting on his envelop shaped hat and he walked out the door. I knew that my dad was in the NY Army National Guard. I didn’t know what exactly that meant, but I had been forced to memorize those words in case I was lost and needed help finding him. I also knew he had fought in a war called Vietnam. He had many of pictures in our den of himself, but younger, smiling and holding guns with men I didn’t know or had never seen before. There was one picture I was fascinated by. It was a black and white picture of a beautiful young woman dressed in a really short dress with tall, white boots. She had signed the picture, “To Ronnie with love, Ann Margaret.” Ronnie was the name my mom called him so I thought it must be his old girlfriend. He told me he had driven her and someone named Bob Hope around Vietnam during what he called his “second tour”. He said she was very nice and beautiful, but I was not allowed to touch the picture.

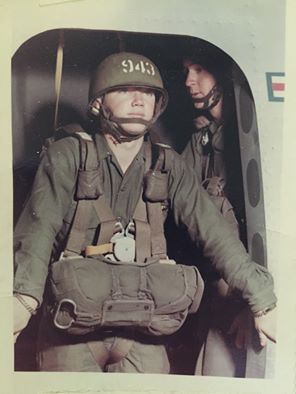

My other favorite picture was of him standing in an open doorway of an airplane getting ready to jump out. He said he was a paratrooper and that was part of his job in the Army. He had jumped hundreds of times and that was why his knees were “shot”.

My other favorite picture was of him standing in an open doorway of an airplane getting ready to jump out. He said he was a paratrooper and that was part of his job in the Army. He had jumped hundreds of times and that was why his knees were “shot”.

He didn’t like to answer questions like, “Did you have to shoot anyone? or Did anyone shoot you?”

He did however, like to share funny stories. I had many favorites I asked him to retell often. One was about someone called “Mamasan” feeding him a really good meal of fried rice. When he asked her what was in it, she motioned to the mice scurrying past the kitchen door. The thought always turned my stomach, but he said it tasted so much better than the canned C-ration of pork and beans the Army served him. He didn’t care what was in it. He said anything was better than C-rations.

I only heard him tell the story of his pet monkey one time, but it stood out to me the most and I remembered it in full detail. The monkey was handed to his best friend Jake by someone he referred to as a “gook”. He said the monkey went everywhere with him and Jake in Vietnam for about three months. When I asked what happened to the monkey he told me he had bitten someone in a bar.

“ A bar?” I asked incredulously.

“Yeah, the girls loved him. It helped me meet a lot of them.” I didn’t like thinking of him with anyone but my mom.

“What did he do at the bar? Wasn’t he bored?” I had never been to a bar, but I imagined it to be like the saloons in the John Wayne movies he watched every weekend. Just men drinking mugs of beer sitting quietly until someone stormed through the doors with a gun. I couldn’t sit quietly so the thought had no appeal to me. My dad smiled remembering, “He drank beer.”

I laughed. “A monkey can’t drink beer.”

“Yes they can! That monkey used to get drunk and…” then he drifted off. He looked at me like he was sizing me up for a minute and he said, “You’re too young to hear the rest of that.”

“So what happened to the monkey?”

“He became a liability and we had to get rid of him.”

I didn’t know what a liability was but it sounded bad.

“Did you kill him?” I asked. He shook his head.

“No, Jake and I just dropped him off on the edge of the jungle. Actually, he tried to bite Jake and Jake said he had enough. He took the monkey and threw him out the window. I watched him roll over and over again until he stood up and ran off.”

I imagined the monkey went back to his own life just like my dad did when he left the place he called a beautiful country.

I liked his animal stories best and one I heard over and over again was the time he went into his bunker and was shocked to see a Cobra rise up at him. He described the black snake with a wing like head in such detail I could see the moment clearly in my brain. He said the snake was coiled up but he knew he had to be close to 13 feet long. He would walk from one side of the room to the other to demonstrate how long the snake would have been had he not been coiled. My eyes grew wide and I shuddered every time he described it. He turned to run out of the bunker, but the other guys were trying to get in to escape an enemy attack and he was yelling, “Cobra! Cobra!” trying to escape the bunker as fast as he could. He ended the story the same way every time. “And that is why I hate snakes more than anything.” I didn’t know where Vietnam was, but it sure sounded exciting to me.

At nine, I also didn’t know much about what he did at work, but I always assumed he was having the same kind of fun adventures just without the guns. I knew that Tuesday night was drill night and that he didn’t arrive home until after my brother and I were in bed. I could never go to sleep though until I knew he was home safely. I wouldn’t see him until the next morning, but I wanted him to tell me more about the exciting news he had shared at dinner the previous night.

He had arrived home unusually happy.

“I found out today that Governor Rockefeller is giving me the medal of valor for saving Chuck’s life.” Mom’s eyes grew big and she grew very excited for him. She jumped up from her chair and hugged him. I looked at him curiously. Wasn’t Governor Rockefeller that crooked son of a bitch, as my grandfather called him? I couldn’t say that out loud though.

“What does that mean dad?”

“It means I will get a medal, the highest honor, for what I did.”

“But what does valor mean?”

“It means bravery and honor.”

“How were you brave?”

“Well, Sis I was in an accident and I saved Chuck’s life by getting help.”

I knew that Chuck was his best friend and work buddy. He told funny stories at dinner about the pranks he and Chuck played on each other every day like stealing the others’ lunch and attaching it to the flag pole, or gluing the others’ stapler and tape dispenser to the desk. They traveled together often on recruiting trips and visited a place called The Playboy Club in Buffalo a lot. I didn’t know what kind of club it was, but mom didn’t like him to tell those stories in front of me and my brother. In my head, I always pictured dad and Chuck as the two funny guys on Mash which we watched every night before dinner.

“When were you in an accident?” I asked.

My mother jumped in, “Don’t you remember when you were five and daddy was in the hospital? We went to visit him and you brought him your favorite brown bear to keep him company.”

I nodded, but the memory was fuzzy and I was not sure I remembered anything more than the snow and ice that I thought had caused the accident.

My brother, who was much too little at six to understand any of this said, “I helped when Doug fell off his bike. I think that was brave. Will I get a medal too dad?”

“No, this is a little different. This medal is only given to a few people. It is a very special honor.” He told us that the ceremony was to take place on Friday morning and a party was planned for that same night.

Before he left that Tuesday morning I followed him around the kitchen until I worked up the courage to ask if I would be able to attend. He told me that I was spending the night at my grandparents’ house. Then he kissed me goodbye and left. When I returned home at the end of that weekend, mom and dad seemed very happy but I don’t remember hearing much more about it. The following week dad showed me the newspaper clipping of the governor putting the medal on his neck. I was proud and excited, but only because it seemed to make him happy and I loved seeing him happy more than anything.

Shortly after the ceremony and the newspaper article, life went back to normal. But, I was always fascinated by that silver star shaped medal hanging off a blue ribbon which he had placed in a wooden box with a glass front. An American flag sat in the back folded into a tiny triangle and several other ribbons and medals sat in front of the flag. One day, I noticed an official looking piece of paper sitting on his desk in the den near the box. I picked it up and began reading. It was the official documentation accompanying the medal and it detailed everything about the accident which my father had humbly neglected to share with me. It read:

On Monday, 22 January 1979, Master Sergeant Ronald D. Hemenway and Master Sergeant Charles J. Barbaro were detailed to field test two snowmobiles to be used by the New York Army National Guard, as an aid to the NYARNG Recruiting program. The place chosen to test the machines was the Guilderland Rifle Range. MSG Hemenway took his snowmobile up an incline, MSG Barbaro followed a short time later. What was unknown to either NCO was that the trail they took, dead-ended to a 65 foot cliff which lead to the frozen Guilderland creek. MSG Hemenway, due to the training he received as a paratrooper, managed to roll as he landed on the ice below. Trying to regain his senses and, at the same time, fighting off pain in his right hip, MSG Hemenway attempted to warn MSG Barbaro of his eventual fate. MSG Barbaro, who was carrying more speed up the trail and over the cliff, hit the ice and water, suffering a broken back and left leg and was in danger of drowning. MSG Hemenway, who was in considerable pain and had reached the shore, returned to the icy water to save MSG Barbaro. Realizing the extent of MSG Barbaro’s injuries, MSG Hemenway made him as comfortable as possible and went for help. Suffering pain, MSG Hemenway climbed the 30 foot, ice covered cliff, walked and crawled over a mile in search of help for his fallen comrade. MSG Hemenway’s quick thinking, training, concern, and ability to endure pain, saved MSG Barbaro’s life. MSG Hemenway’s utter disregard for his own safety, his gallantry, courage, and valor are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflects the greatest credit upon himself and the military forces of the State of New York.

At nine, I was impressed but it wasn’t until I was older that I realized what an amazing feat my father had undertaken. Somehow, all of the funny stories he had shared about Vietnam and the National Guard didn’t demonstrate the courage a small piece of paper and a pointed silver star on a blue ribbon exemplified. I wondered then and still wonder today if I would have the ability to scale a cliff in order to rescue my friend. I am sure my father has done many other acts of valor for which he goes unrecognized. His lengthy bio of service to our country more than illustrates the valor he has demonstrated in his lifetime.

Ronald Hemenway served in the US Army active duty from 1967-1972 and completed two tours in Vietnam from 1967-1969. He then joined the NY Army National Guard where he served from 1973-1993. He initially served as a combat engineer and eventually was promoted to the head of recruiting and retention for the state of NY. In 1985 he was promoted to the rank of E-9 becoming the youngest person ever to receive the promotion to Sergeant Major. During his service he has received over 40 individual medals, as well as the medal of valor. Following his retirement, he served as a materials expediter at DDCN, Defense Depot Cherry Point. After four deployments to Iraq with the DDCN, he was issued the Secretary of Defense medal for the Global War on Terrorism in 2009. He is also a self-published author of three fantasy fiction genre novels he completed in his spare time without ever having taken any sort of creative writing class. All of this is why I define Sergeant Major Hemenway as a man whose entire being demonstrates “gallantry, courage, and valor” and I couldn’t be more proud of the man I also call dad.

Bridget Floyd has been an English instructor at Cape Fear Community College for thirteen years. She received her BS in Communications from East Carolina University as well as her MA in English with a concentration in Creative Writing. Surrounded by military family most of her life, Bridget had often wished to serve as well, but couldn’t due to a congenital heart defect. She did however participate in the Civil Air Patrol throughout high school allowing her to fly a Cessna before driving a car, stand guard over an F-16, and meet the Blue Angels. Her military roots and love for writing make her a huge advocate of veterans sharing their stories, and she is honored to be included in this special group of writers.